Why We Fight

22 April 2011

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (City, that is) recently announced the successful restoration of an audio recording of a speech Dwight D. Eisenhower gave at the museum in April of 1946. General Eisenhower’s speech was part of the Met’s 75th Anniversary wherein he was being honored for his role in overseeing the protection and repatriation of monuments and artworks during and after World War II as performed by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section of the allied armies (MFAA).

The audio was recorded on glass-based lacquer discs — a highly fragile format that, like most lacquer discs, is at severe risk for chemical and physical degradation. Last year the Met received a grant from The Monument Mens Foundation, an organization dedicated to honoring the work done by the MFAA and continuing to support the protection and repatriation of art works in areas of armed conflict, to preserve the audio and make it accessible to the public. Our own Chris Lacinak was very honored to be one of a group of professional advisors who provided the Met with guidance on planning their restoration.

As always, it’s great to see a successful preservation project completed, and, going beyond Eisenhower, the story and (continuing) mission of the Monuments Men is fascinating, essential history. On a personal level, however, what this story brought back to me was a memory of what a scapegoat Eisenhower was when I was growing up — the middle-of-the-road, middle-of-America, caucasian patriarch who was the symbol of the hegemonic complacency our parents were oppressed with. Perhaps an exaggerated response considering the other forms of oppression occurring in the 1950s, but for years those too-brightly-lit, kinescope-distorted, early television images of Eisenhower in close up went hand-in-hand with scenes of mushroom clouds and children ducking under desks in various documentaries or other uses of stock footage.

But then something started to happen. Saving Private Ryan and The Greatest Generation made Boomers start to reconsider their parents’ lives. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq made people think about how the military is run and the president’s role as commander-in-chief outside the emotions caused by Vietnam. Eisenhower’s farewell speech, which included the warning about the military/industrial complex, became an ur-text of liberal politics. The past from my past became a different past as the interpretive position shifted from the heat of one moment to the glow of hindsight and the heat of another moment.

The cycle of generational context would suggest that I scoff at such softening as I continue to cling to my childhood anger at the dismantling of social, educational, and arts support in the 1980s. Reagan, too, has been making a comeback of late as both sides of the aisle fight over who best represents his ideology and his legacy. Either I’m a stubborn-headed fool or this is a good sign that I’m not too old yet.

A commonality in these parallel trends is the use of audiovisual materials to support reassessments — televised speeches, recorded visits of state, audio interviews — all of it easily distributable, easily accessible content. A commonality in this commonality is that, for the most part, one can assume these recordings come from major events covered by major news outlets. This is far from an assurance that such recordings would always be preserved, but, if they were, they would be and become part of the common cultural memory. Be because of the significant audience at the time. Become because of the repeated airplay they may receive in documentaries and news stories, a situation which can create a familiarity that causes people to believe they experienced the event the first time around…which then promulgates further reiteration of the same footage, becoming a visual shorthand for wide swaths of history. To half-misinterpret the old saw about Woodstock — if you remember being there you probably weren’t.

To me, this pseudo-echo effect has two meanings. First, audiovisual content is so powerful that it can embed itself in our memory quite easily. Second, we need to dig deeper with our support of smaller local, regional, or institutional archives and historical societies in order to uncover new stories that create a fuller picture of the past. The Eisenhower recording at The Met is a great example of this. DDE’s work with the MFAA, while incredibly important, has not been a major part of the wider representation of his military and political career. Thanks to The Met and the Monuments Men, we now have a greater understanding the career and the man.

One can also look to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s American Archive project, which is poised to uncover loads of locally produced programming that will be highly meaningful to our understanding of broadcast history and American culture, and as equally impactful to the pleasure we derive from both. Or among some recent clients I’ve worked with, one might look to institutions like Hartwick College in upstate New York whose archives contain a treasure trove of regional oral histories and audio or video recordings from the numerous scholars, artists, and cultural figures who have spoken at the college. Or the Tenement Museum‘s extensive oral history collection of Lower East Side residents, material that can be used to support research as well as the creation of exhibits and educational material which support the Museum’s mission.

It seems so common to repeat that humans and history are complex and deserve the full picture archival material can provide. Common, but worth restating because it is so easy to take for granted that archiving just happens, that of course everyone is taking care of their stuff because it is so valuable and that all that material is easy to find and use. Archiving is more than putting items in a box on a shelf. It requires active planning, management, advocacy, and promotion. As the MFAA and the military were aware, archiving and preservation do not happen unless we make them happen, unless we enable them to happen, unless we demand they happen. I reckon they were a might good generation after all.

Azimuth Adjustment For Magnetic Audio Recordings By Audrey Young And Peter Oleksik

14 April 2011

The ease of using cassette-based media — pop it in and press play — and the development of compact, no-frills consumer electronics helped make audiovisual materials more accessible to a wider population, but there has also been the side effect of distancing users from the processes involved in recording and playback that were more apparent with open reel media and higher end decks. This is less of an issue with commercially recorded tape where standards are more regulated, but when dealing with field recordings, oral histories, and other original material, the configurations and settings of the recording device and playback device can have a major impact on audio or visual quality if unaccounted for.

In the first in a series exploring all of those knobs, switches, and buttons you see on decks, Audrey Young and our own Peter Oleksik have written a brief primer on azimuth and why it matters for archivists, researchers, and other people who listen to or work with magnetic audio recordings.

Noting Screening The Future

12 April 2011

While our own Dave Rice was presenting on a panel at the recent Screening the Future symposium in The Netherlands, newest AVPS team member Kara Van Malssen was herself on hand to participate and learn. Here’s her review of the doings that transpired:

Screening the Future

15-16 March 2011

Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, Hilversum

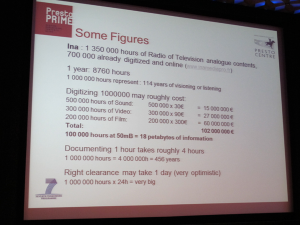

Screening the Future: New Challenges and Strategies in Audiovisual Archiving was an intensive two-day event on common challenges and solutions in the audiovisual heritage domain, held at the spectacular Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision in Hilversum. In a tightly packed schedule, 22 practitioners spoke on digitisation, workflows, digital preservation, sustainability, funding, improving access, and much more. The event marked the launch of the PrestoCentre, a new competence center for digital audiovisual preservation in Europe. A result of the successful European Presto project series (including the completed PrestoSpace and ongoing PrestoPRIME projects), PrestoCentre is a non-profit membership organization which will “provide analysis and advice to custodians and creators of audiovisual content, through online and offline services, publications and training.” There is already a wealth of useful information on their website, which is sure to grow into an indispensable resource for audiovisual archive professionals.

The conference celebrated the successful transition that many European audiovisual archives have made into the digital realm, while simultaneously sparking debate on the many ongoing challenges that these organizations still face: How can we valorize our archives? How can we fund ongoing digital preservation? How can we become more efficient? How should we approach the collection of the flood of born-digital (especially user generated) content that is not currently addressed by traditional heritage organizations? These are big questions, without simple answers.

There was quite a range of topics and speakers. However, given that it was a European event to celebrate European projects and progress, it was interesting to note that a large number of speakers were North American (or based in North America – such as the case of David Rosenthal, British, based in California). Also noteworthy was that only one woman speaker graced the stage over the course of two days (women, we can do better!). In any case, the expertise and experience of all the speakers was inspiring, and nicely balanced technical talks (like the presentation of new preservation planning tools from the IT Innovation Centre in the UK) with broad strokes.

Full presentation available here.

My personal top three presentations of the event addressed complex issues, sparked debate, and were energetic. I felt they left us with a charge, a task to improve, a direction to move toward.

———-

Peter Kaufman’s (Intelligent Television) keynote “Towards a New Enlightenment: Moving Images, Recorded Sound, and the Promise of New Technology” presented an overview of the landscape that audiovisual archives are entering as we move into the digital age, one in which audiovisual content is of equal or greater value than the textual asset (where, in fact, differences of media are evaporating altogether). Referencing Kevin Kelly’s new book, What Technology Wants, Peter whet the audience’s appetite with the notion that the millions of recorded sounds, images that archives are contributing to the web are fueling the electronic mind of the growing planetary electric membrane; we are contributing to the collective synthetic intelligence each time we give a name to an image online, or when we click a link. This global super computer is getting smarter everyday, and video is increasingly becoming part of that intelligence. With new tools like HTML5 and popcorn.js (live web citation and analysis of video content!), video is becoming a more integrated part of the web. There is enormous potential yet to come.

With that introduction, Peter offered 6 recommendations for the PrestoCentre, to help its members build together toward a “Digital Renaissance” – referencing the important recent publication by the European Comité de Sage – rather than a digital dark age. In sum:

- Engage our publics. Peter and Paul Gerhart have been working on this for the JISC-funded project, Film and Sound in Higher and Future Education. This is a marketing challenge, but one that AV archives cannot ignore.

- Engage with Technology. Make our content completely discoverable. Enabling resource discovery is a technical challenge, and involves applying relevant metadata. Users find that the range of user interfaces, search terms, and classifications make it difficult to find what they need. The commercial sector is exploiting the potential of recommendation engines (e.g. Pandora, Netflix). Can we learn from what they do? Google images can search automatically on rights embedded metadata. Wikipedia can crawl and ingest Flickr images that are Creative Commons-licensed. Peter’s recommendation: Develop a research and action plan for engaging with Google and other resources that make content discoverable.

- Facilitate use, clear rights. In order to achieve this, we must collaborate with current owners and their lawyers. Systematically set out the obstacles to making AV content available to education. Using new technology (like popcorn.js) we can actually identify rights holders, unions, and other contributors to a work, and…promote them! Give them credit where credit is due! A novel idea.

- Work with producers. Archival content begins as the point of creation. In the digital era, we can’t afford not to work with them.

- Work with business. Collectively determine best practices for public-private partnerships in AV heritage.

- And one bonus: Work with Americans! (We need your help!)

———-

Brewster Kahle’s energetic presentation, “Scaling Up, Scaling Down: Making the Most of What We Have,” on building cost effective digitization workflows and data centers for large scale digitization preservation had the audience hanging on to his every word (Brewster is certainly one of the most compelling speakers I’ve ever had the pleasure of listening to). His talk was framed around the work that has been accomplished by the Internet Archive (Millions of books digitized! The entire web archived!) on essentially a shoestring budget. Taking a bit of a jab at the Europeans, he pointed out that “large amounts of money give us excuses to not do things.” By focusing on efficiency and lowering costs, the Internet Archive is now able to mass digitize video at $15/hour and film at $200/hour. Off-air television is captured for very little, with Electronic Programming Guide and Closed Caption data extracted to improve searchability. He admits that it takes a lot of money up front to get started, but there are a number of ways to reduce costs over the long-term, such as leveraging the infrastructure of partners, and using your data center to heat your building(!). The Internet Archive measures its own progress in terms of bits in and bits out, and they are doing quite well: outbound they have 10 Gb/s of bandwidth being accessed by 2 million users each day. They are the 200th most popular site on the web, despite the fact that their “user interface is as bad as it gets.” The Internet Archive has so successfully built a cost-effective infrastructure that they can down offer cloud storage, at a cost of 1 terabyte for $2000….forever. That’s a one time payment folks.

Brewster had a lot to say about access as well. He discussed their business model, and how they are able to sustain themselves using a “free to all” access policy. He noted that, “archives make terrible business models,” and argued programs like digital lending are working, without getting the attorneys all heated up. He challenged the audience to think about their mandate as archives: are we just the preservation people, or are we the ones who are going to make stuff available on iPads? With a resounding “shame on us” he chided archives for keeping the best of what we have to offer in our basements, away from the reach of children who learn from what they can find on the Internet. We are not just archives anymore, we must be libraries too. Brewster is ready and willing to partner (for large scale data backup swaps), to offer services (digitization, storage, access), and he is going to do it cheaper and faster than most other organizations. His conclusion: “We get more done because we have less money than you.”

———-

The entire morning of the second day was a panel on “Building Workflows for Digitization and Digital Preservation,” which paired presentations from service providers (Michel Merten, Memnon; Jim Lindner, Media Matters) with representatives from some very large audiovisual archives (Daniel Teruggi, INA; Tobias Golodnoff, Danish Radio; Tom de Smet, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision; James Snyder, Library of Congress). At first, I found it surprising that a large portion of the conference was devoted to digitization. After these talks, however, I realized that rather than a series of questions about the challenges of digitization, which has been the focus of many presentations over the past several years, these were digitization success stories: after years of trial and error, millions of hours of audiovisual heritage have been digitized. Something to be proud of, but we still have a long way to go.

Of these talks, I found Jim Lindner’s presentation on improving digitization workflows particularly useful. Jim’s simple argument is that by evaluating every point in the chain, by measuring bottlenecks, we can realized increased efficiencies. Sounds obvious, but turns out to be rarely practiced. Quite often, he finds that the problem isn’t where you might think it is, but perhaps further up the chain. Dependencies in the workflow mean you must untangle entire thing to find the problem, and then fix it.

Jim’s message is to take cues from the real world – security lines at airports, traffic, McDonalds – where efficiency is paramount. Business management and manufacturing literature can be particularly useful to the audiovisual sector. He recommended a number of books (Brussee’s Statistics for Six Sigma Made Easy, Womack and Jones Lean Thinking) but stressed that if you are just going to read one business book, make sure it’s The Goal by Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s (author of Theory of Constraints). Goldratt, and Lindner, press the need to look at the entire system, and identify the constraints, or bottlenecks. These are the places to measure things.

To illustrate the method, Jim used a typical audiovisual digitization workflow, which follows a process of accession → selection → digitization. Most archives perform selection because digitization is expensive, therefore, we shouldn’t digitize everything. But in this workflow, a backlog begins to form, and it isn’t at the digitization stage, where one might assume, but at the selection stage. Turns out, selection requires a surprising number of steps and individuals: choose tapes for selection; identify extant viewing copies, if any; generate viewing copies; view copy; catalog. If there is any bottleneck in this sequential process chain (unable to find copy, no machine to create copy), work stops proceeding. Thus, if we re-examine the overall goal, and look at the available tools to support the entire workflow, it might just make more sense to do the selection on the digital side.

———-

At the conclusion of the event, the moderator, Bernard Smith, along with Jeff Ubois, reviewed the conference themes, and asked the audience if we felt they were adequately covered. Do we know what we are preserving, and are we making the right choices? Have we developed good practices for working with the private sector? Do we have adequate funding models for sustainable digital preservation? Do we know how to best valorize our collections in today’s evolving landscape? The answer was a resounding NO. We have a lot of work left to do. Here’s hoping we’ll reconvene next year to revisit these issues and see how much progress we’ve made.

— Kara Van Malshttps://www.weareavp.com/team/kara-van-malssen/sen

AVPS Welcomes Kara Van Malssen

5 April 2011

AVPS is proud to announce the addition of our newest team member, Kara Van Malssen. Kara joins us from Broadway Video Digital Media where she was Manager of Archive Research on the Corporation for Public Broadcasting American Archive Strategy Consultancy. Kara is a 2006 graduate of NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, and she has held consultancies with CPB, National Public Radio, and the Museum of Modern Art, and previously worked as a Metadata and Digital Preservation Specialist in a joint project between NYU and public television broadcasters. She maintains strong interests in audiovisual preservation training and international outreach — having been invited to teach instructional sessions in Ghana, Mexico, India, and Lithuania — and also blogs on world cuisine at The Confined Nomad: Eating the UN, from A-Z, without Leaving NYC.

We have had the pleasure of working in tandem with Kara over the years on projects related to metadata development, digital preservation, and repository development, and we have always admired her skillz, strong character, outgoing nature, and wide range of personal interests. We’re extremely happy to have her join us now and look forward to the exciting opportunities ahead.